The expansion of mobile access has been a common refrain in international development for years now. It plays an important role in supporting human development, from economic and educational opportunities to political freedoms and human rights. Increased access to mobiles has been linked to positive social outcomes in dozens of countries.

Context is King: Knowledge Sharing on Communications Tools at BBC Media Action

By Amy O’Donnell, FrontlineSMS:Radio Manager

By Amy O’Donnell, FrontlineSMS:Radio Manager

Recently my colleague Flo and I visited BBC Media Action for a Knowledge Sharing session which focused on the use of innovative mobile technology to enable effective communication for social change. BBC Media Action (previously known as the World Service Trust) "uses media and communication to provide access to information and create platforms to enable some of the poorest people in the world to take part in community life. With a focus on programming that directly engages people in debate and discussion thereby encouraging communication across political, ethnic, religious and other divides in society." We felt lucky to be one of the last visitors to their longstanding home in the iconic Bush House, London as the BBC is relocating from there after 70 years.

Often when people first hear about FrontlineSMS, it’s not just the software which inspires them, but the valuable lessons we learn from how the tool is being used. BBC Media Action works to directly engage people in debate and discussion through programming and this workshop explored the potential of SMS to open up participation.

To broaden participation, combine accessible communications channels

We explored how a radio station in Uganda is using FrontlineSMS to gather incoming audience feedback via SMS to put their questions to MPs while on-air; how FrontlineSMS is engaging citizen journalists in Indonesia and how the software is being used to run a news service for women in Sri Lanka. Introducing another popular open-source platform, we explained how the Ushahidi mapping tool was used in conjunction with FrontlineSMS for election monitoring by the Reclaim Naija project in Nigeria last year to illustrate reports in relation to their location. Many of these programs use SMS in concert with other platforms, whether radio, TV or the Internet - an important element of building a truly accessible, system that works for its unique context.

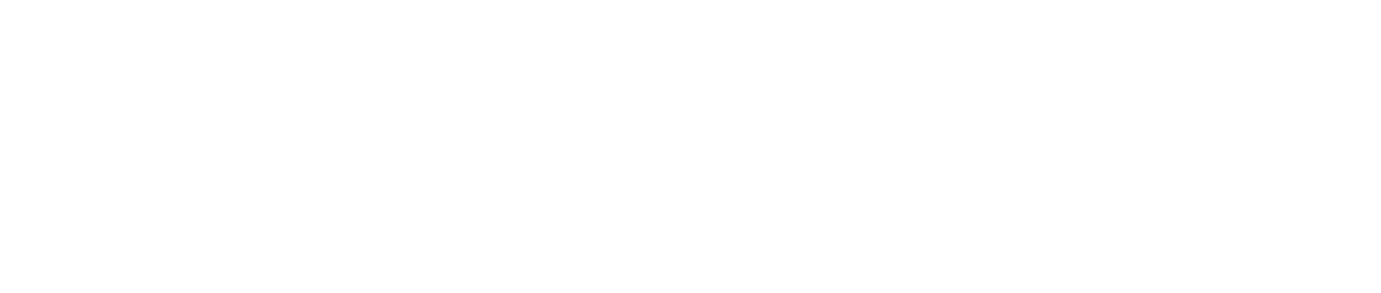

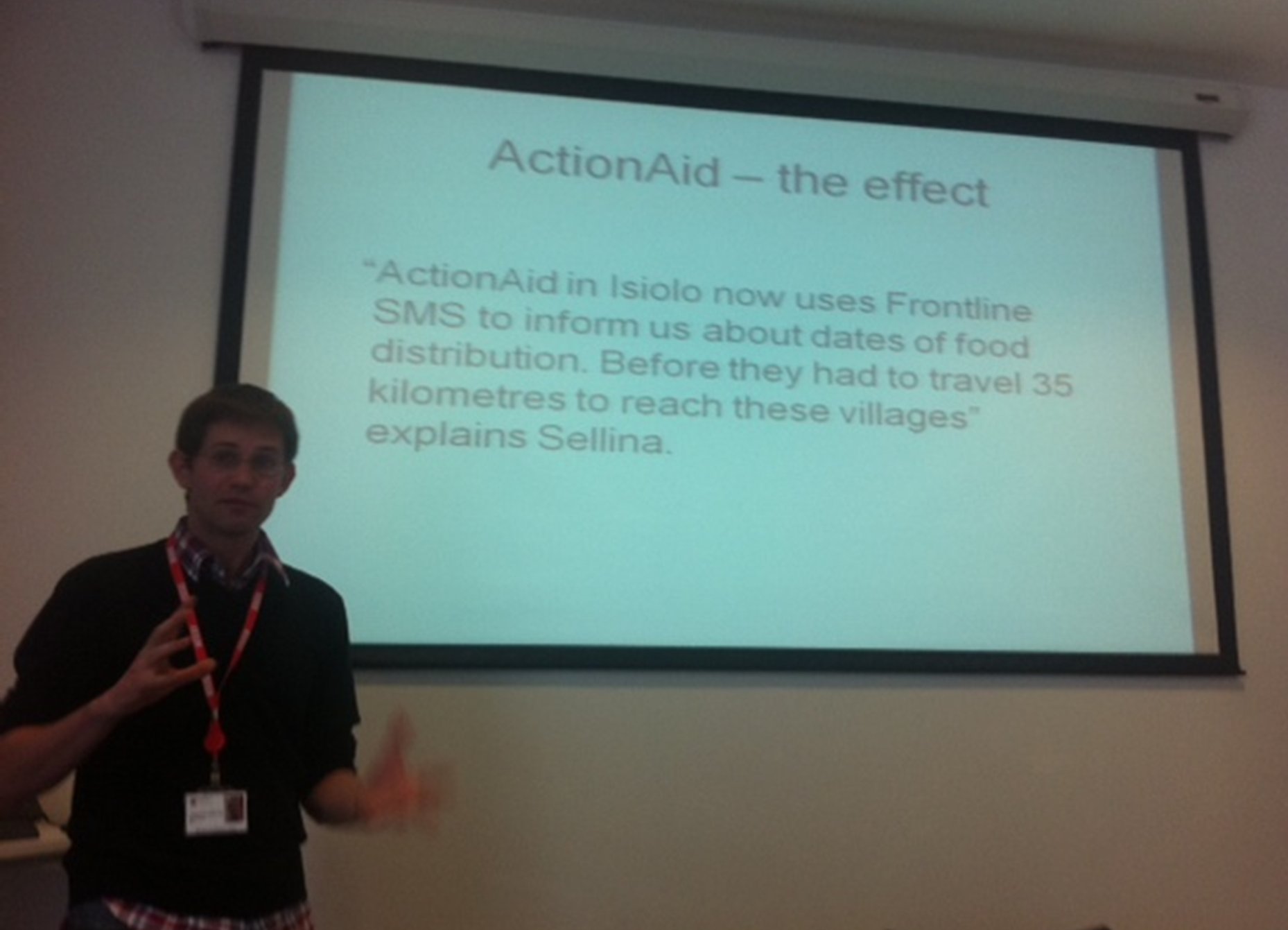

BBC Media Action’s own Jonathan Robertshaw shared his experience of using FrontlineSMS as a practitioner. He explained BBC Media Action’s role in a project run by ActionAid and infoasaid which which set up a food distribution alert and food price information system in Kenya in the aftermath of the 2011 drought. The project successfully took a multi-platform approach to improving communication between relief committees, food monitors and the public. The set-up gave people options, including voice (using an interactive voice-based software called FreedomFone); detailed SMS-based data collection (using FrontlineForms, FrontlineSMS’ data collection tool); and text message (using FrontlineSMS’s core platform).

Technology is 10% of the solution

As the discussion with different Media Action project leaders delved into program specifics, we explored how technology often only represents a small proportion of overall project design. Looking at potential Media Action projects - including participatory audio dramas and humanitarian radio - reinforced how important it is not to lose sight of behavioral and cultural factors as well as critical delivery planning: outreach, messaging, integration, translation, verification and impact monitoring. One of the group asked how to anticipate the resources required to run a communication platform. Particularly when the volume of response depends on the level of interactive behavior, the group agreed there is no “one-size-fits-all” or “magic formula.” Program staff have to consider the context and stay flexible, tweaking the system to respond to the needs of their beneficiaries and staff as they develop. Resourcing this kind of responsiveness is critical and difficult, and there are costs in money and goodwill involved in introducing people to a new system, changing messages and systems too often. The group agreed that, rather than committing to services which it may be difficult to estimate demand for, organizations should manage expectations and try to test ahead of time. Trying out communications in small trials or pilots can help scope people’s reactions.

The strongest message we took away from the session was practitioners’ motivation to learn about the different tools available in the communications toolkit. Often the design of a communication system is not about one tool, but the right tool or right combination of tools which suit the context. FrontlineSMS needs limited support and people are implementing projects all over the world using the software and tools readily available to them without requiring our team’s direct involvement. We're proud of how much that makes it a really sustainable piece of software for organizations working in the last mile, and a critical tool for long-term capacity-building.

Technology Meets Humanitarian Response

Over the last two years, we have worked to raise awareness of the potential of SMS, and FrontlineSMS, as a sustainable, capacity-building tool in humanitarian response. We have documented how our software is being used to manage and coordinate aid responses by a wide variety of organizations - including OCHA, Action Aid and Infoasaid, European Disaster Volunteers, Popular Engagement Policy Lab – and in a range of contexts - including Kenya, Pakistan and Haiti. We have also produced a tailored checklist on what to consider when planning use of mobile technology for humanitarian response. All of this content is representative of a more general trend; that of a growing number of humanitarian organizations keen to engage with how ICTs can help support their work.

In March 2012, we participated in two events in London which demonstrated this increasing interest. The first, a two-day Media and Tech Fair hosted by the Communicating with Disaster Affected Communities Network (CDAC), showcased technologists and implementers from all over the world, sharing with an audience of CEOs and decision-makers how their solutions and pilots have begun to change the way they engage and communicate with the people they work to help. The second day of this event featured practical workshops and scenario-based discussions, intended to help people to think through how they could put these tools and approaches into practice on the ground.

The second was an afternoon event - co-hosted by the Overseas Development Institute (ODI), Active Learning Network for Accountability and Performance in Humanitarian Action (ALNAP) and the Cash and Learning Partnership (CaLP) - launched an excellent report written by the team at Concern UK: New Technologies in Cash Transfer Programming and Humanitarian Assistance. Our Director of Operations, Laura Walker Hudson, participated in a panel discussion reflecting on the themes raised in the report, and we were pleased to have had the opportunity to have contributed to Concern’s research.

The report takes an in-depth look at the current use of new technology in humanitarian cash and voucher programming, and the broader implications this has for humanitarian practice. In addition to some positive cross-cutting themes – such as the improved accountability and cost-effectiveness which can result from successful use of technology in humanitarian work – the report also contains advice on mitigating some of the challenges that still obstruct wider implementation. The result is a thoughtful and broad-based survey of the opportunities and challenges facing humanitarian agencies in selecting and rolling out technological tools - reflections which are valuable across all sectors, not just humanitarian aid, for their honesty in assessing institutional barriers to change and innovation. We will examine some of these issues in a future post, and consider their relevance for anyone trying to mobilize information management and communications.

For now, a few broad themes recurred in both events:

- Disaster affected populations are already utilizing ICTs on the ground, and the globalized nature of news and volunteerism means that groups like the Standby Taskforce are pitching in to help manage and process data. If agencies fail to acknowledge progress made by others, they will be left behind.

- Erik Hersman, one of the founders of Ushahidi, reiterated a core value we share in his keynote summary of the first day of the CDAC event: technology is only a small part of what needs to be considered in planning discussions; the context, the program design, training and sustainability, and most importantly, listening to the people the project seeks to help, are a larger part of the effort and critical to success.

- The critical importance of cross-sectoral and inter-agency collaboration recurred again and again, at both events. To avoid duplication of effort, conflicting data standards, wasted resources and crowded information marketplaces in emergencies, key stakeholders must work together, and seek to understand others’ perspectives in a rapidly evolving area. Working in a consortium, or creating open-source tools available to everyone, could potentially speed up development of useful platforms and improved learning about what works and what doesn’t. Collaborating effectively with the private sector and with technologists could far more effectively harness additional resources and intellectual capital, and a coordinated ask of major players, such as the GSMA, is crucial - but can feel impossible to secure.

All in all, the humanitarian sector has a long way to go, particularly at head office level, but our team was left with a sense that there are a growing number of humanitarians who are taking an agile, open and open-minded approach to trialling new tools and sharing their findings with others. Yet it is at field and regional level that the real innovation is happening, away from the overlapping priorities and initiative overload that characterizes the global management hubs in New York, London and Geneva. As ICTs in humanitarian aid become more commonplace and begin to integrate more fully into the standard agency toolkit, agencies, technologists and the private sector must continue to build relationships and exchange information in order to build sustainable, coordinated, and appropriate use of technology in humanitarian response.

Following both of these events, valuable resources have been made available online:

CDAC event:

- All videos, photos, case studies and resources from the day can now be found online

- Case studies featuring FrontlineSMS use include:

- Using FrontlineSMS for a complaints and response mechanism after the Pakistan floods

- Infoasaid and Action Aid partnership and communications initiative in Kenya

- International Organization for Migration - Flood Affected Citizens Damage Compensation Program (whose use of FrontlineSMS we covered on our blog here)

ODI and CaLP event:

- New Technologies and Cash Transfer Programming in Humanitarian Assitance Report

- Videos from the panel discussion at this event, including our very own Laura Walker Hudson

Sending a Message of Accountability: SMS Helps Improve Services After Pakistan Floods

In this guest post, Alex Gilchrist explains how the Popular Engagement Policy Lab (PEPL) used SMS to communicate with affected communities during the humanitarian response to the floods in Pakistan in 2011. Using FrontlineSMS to set up a Complaints and Response Mechanism, people were able to share their experiences of accessing food and shelter. Co-authored by Syed Azhar Shah from Raabta Consultants, this post demonstrates how it is through the effective use of communications technology that people can be connected to the services they need the most. Guest Post by Alex Gilchrist, Popular Engagement Policy Lab and Syed Azhar Shah, Raabta Consultants

The 2011 monsoon flooding in Sindh, Pakistan’s southernmost province, affected an estimated 5.5 million people. The floods compounded the damage caused by flooding in 2010 and the lack of clean drinking water, food, healthcare and shelter resulted in communicable and non-communicable diseases across the province. It also caused loss of livelihoods through damage to agricultural land and death of livestock that will continue to affect the lives of the people of Sindh for years to come.

In the aftermath of the recent flooding, a large Pakistani NGO called Strengthening Participatory Organisation (SPO), which manages a network of organizations across Sindh province started a new project in Mirpur Khas district, distributing food items and shelter to those worse affected. Following an assessment process for one of its smaller projects, SPO selected a total of 475 beneficiaries across 24 villages.

A concern of SPO’s head office in Islamabad was that complaints and feedback from beneficiaries in previous projects had not been documented or dealt with effectively and they wanted to monitor the distribution process. This is when the Popular Engagement Policy Lab (PEPL) and Raabta Consultants were asked to help.

We were asked to set up a mechanism through which people could register issues they encountered during the flood relief distribution project in order to improve accountability and transparency before, during and after the distribution had taken place. PEPL develop research methodologies, specializing in innovative uses of low- and high-tech information systems, and for this project we collaborated with Raabta Consultants, who help communities in Pakistan to access the valuable social services provided by governments, NGOs, charities and the private sector. Using FrontlineSMS, we developed a system to handle SMS-based feedback from affected communities as part of their new Complaints and Response Mechanism (CRM).

Although less than half of Pakistan’s population owns a mobile handset, recent research indicates that more than 70 percent of people have regular access to a mobile phone. Amongst phone owners in the poorest 60 percent of Pakistan’s population, 51 percent of men and 33 percent of women used SMS, according to a survey by LIRNEasi in 2009. We wanted to test whether we could harness the prevalence of mobiles and the use of SMS for improved accountability.

Beneficiaries of the project were selected in virtue of being the most disadvantaged in each village: often those with disabilities; child-headed households; or female-headed households, and literacy rates among them were low. We realized it would be a challenge to design a system that would be accessible and useful across the board. To put these concerns to the test, we conducted a questionnaire involving participants of both genders on mobile phone usage. To the surprise of the project team the overwhelming response was that access to mobile phones was widespread, and if someone did not own a mobile phone then they could borrow one from a family member, friend or even village council member and even ask someone to write a message on their behalf. Through this evidence about the culture of using mobile, we gained overwhelming support for a system to base the CRM on a combination of text messages and voice calls.

The next step was to configure a system using FrontlineSMS so that people could text us requesting a call back. Sindhi is largely written in Arabic text, but not all handsets can recognize the Unicode in which it appears. So, following the conversations with villagers, the team devised a numbering system for complaints ranging from 1-0. The code was as follows: 1 = Food items, 2 = Shelter, 3 = Conflict 4 = Corruption, 5 = Issues with SPO staff, 6 = Issues with Partner Organisation staff, 7 = Issues with Village Council, 8 = Issues affecting women and children, 9 = Issues affecting those with disabilities, and 0 as a means of saying “thank you”. This numbering system allowed for automatic replies through FrontlineSMS tailored to the complaint, as well as a response time.

The numbering system was printed on cards with corresponding pictures, and the SMS and feedback system was also explained through diagrams. On the cards we included telephone numbers for verbal complaints and instructions for written complaints. Having printed out leaflets, posters and cards the teams went to every village and explained the process to beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries alike. During this process, field workers documented all beneficiary phone numbers or relatives’ and friends’ phone numbers, which were then saved in FrontlineSMS. This meant that every message received in FrontlineSMS would also have a name attached to it, and the system was set up so that every auto reply contained the name of the sender. We believe that the in-person relationship is a critical step that makes the difference in the popular uptake of a communications system.

Through the groups feature on FrontlineSMS, we created lists for village and Union Council members so that before each aid distribution process SPO could send messages alerting the beneficiaries about its arrival, and following the distribution process we could actively solicit feedback via SMS. When a message was received, the response manager would call back, ask for more information and then follow the internal complaints procedure.

Over the three-month aid distribution project we received 725 messages, 456 of which followed the numbering system. The awareness of this system amongst partner organizations and project staff meant that they knew they were being held to account for their actions, so it ensured the quality of their work. It was especially important that the system protected the identity and data of participants in a way that could not be tampered with. Fundamentally, we learnt that giving people a direct means with which to register a complaint or feedback empowered the beneficiaries of the relief effort to have a say in the way they were treated and furthermore to be connected with organizations who could offer further support.

Supporting disaster affected communities in Haiti using FrontlineSMS

Guest post from Andy Chaggar, Executive Director of European Disaster Volunteers (EDV) who are using FrontlineSMS in Haiti:

European Disaster Volunteers' mission is to help disaster affected communities worldwide achieve sustainable recovery. This means doing more than simply addressing the damage caused by disasters; it also means addressing the underlying, long-term factors that made communities vulnerable in the first place.

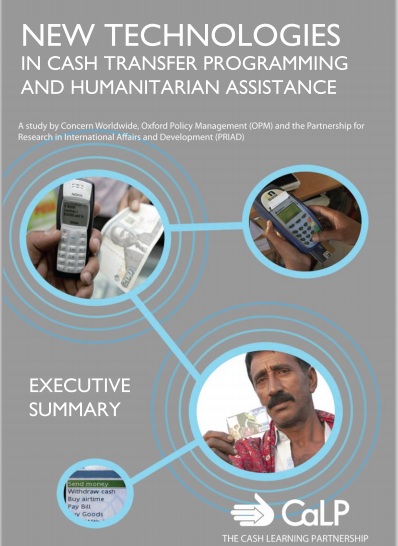

We’ve been working in Port-au-Prince, Haiti since June 2010 and have placed a high priority on education since the beginning. EDV has rebuilt or repaired 36 classrooms in eight schools, are providing scholarships to 50 primary school children, and also run free English classes for adults.

Having originally graduated with a degree in electronic engineering in 1999, this work is a major change in direction for me. However, given my previous career it’s probably not surprising that I’ve retained a strong interest in technology, particularly in its application to disasters and development. So, when I heard about FrontlineSMS, I immediately saw its usefulness to EDV’s current work in Haiti.

From the outset I knew FrontlineSMS would be particularly helpful for our English Education program. English is a key vocational skill for Haitians seeking employment and, almost as soon as we arrived, we started getting requests from our community for language support. Over the past 17 months, what began as informal classes has developed into a structured program that includes 120 students in eight weekly classes at four different levels.

Managing communications in the program was a challenge from the outset. In addition to the students, we have to coordinate our Haitian teachers and international volunteers. Everyone needs to be kept informed of the time and location of meetings and scheduled classes are prone to disruption.

In a country like Haiti, everyday issues like teachers being ill are compounded by problems of instability. Potential hurricanes, political unrest or simply a particularly heavy rainstorm all have the ability to disrupt class, so the ability to communicate is vital.

Very few Haitians have regular access to the Internet so group emails aren’t an option. Before using FrontlineSMS, we would often have to scramble to call, or text, everyone affected to reschedule a class. In some cases, such as during heavy rain, an unlucky volunteer would have to walk to a class where we knew very few students would turn up simply to apologise to the few who did and tell them to try again next time.

Now, by using the software’s ability to create contact groups, we can very quickly and cheaply text all students in a given class or call all of our Haitian teachers in for a meeting.

Our English program is very popular and also has a big waiting list. When spots in our various classes recently opened up, we were also able to use FrontlineSMS to text over 100 prospective students and invite them to take a placement test so we could fill the classes with students at the right level.

Overall, this simple but effective technology has made managing our English Program much easier. Without FrontlineSMS, we would still be using chaotic, time-consuming and inefficient methods of communicating, all of which would distract and disrupt the actual work of teaching.

The fact that FrontlineSMS is free is also very appealing to us. While we’re a growing charity, we’re still fairly small and love to save money by using free technology. Beyond this, however, an important principle is at stake. EDV is committed to working with disaster survivors to build local capacity to meet local needs. This partly means connecting survivors with tools they can use themselves. Even if we could afford to buy expensive, licensed software, the survivors we work with never could. As a result, we always prefer to use technology that is as accessible to survivors as it is to us.

We’re in the process of handing over leadership of the English Program to our local teachers and a Haitian school administrator. As part of this process, we’ll be providing a computer with the software and contact groups installed so that our communications solution is transferred. We’ve found using FrontlineSMS to be very intuitive so we’re confident our school administrator will continue to retain and develop use of the technology.

We have other future plans for use of FrontlineSMS in addition to our English Program, and see many ways it can help us operate more effectively. We currently also use the technology for our own internal messaging which is critical in Haiti due to security issues. Political demonstrations can be dangerous and can happen with little warning, so being able to quickly text all of our in-country volunteers and tell them to return to base immediately helps keep everyone safe.

We’ll definitely continue to use FrontlineSMS internally in other disaster zones, and we will continue to explore other potential project-related applications for the technology as well. For example, a couple of years ago I visited a community group in the Philippines who provided early warning alerts to its members living in typhoon and flood prone areas of Manila. While doing an amazing job, they were reliant on an aging infrastructure of radios and loudspeakers and this process could have been strengthened using FrontlineSMS.

I see the need for such early warning systems time and time again and I’m fairly confident that in the future such work could be complemented and improved by using FrontlineSMS to quickly text those in danger. Moving forward, I’m excited to see how FrontlineSMS, and technology overall, can be applied to solve important real-world challenges and both help to save and improve lives.

ReliefWeb: Using text messaging as weapon in malaria war in Cambodia

ReliefWeb have recently reported on FrontlineSMS being used to help to contain the spread of malaria in Cambodia. This story has also received coverage from IRIN, the news service of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. The FrontlineSMS blog featured a guest post about this use of our software, too, which you can read here. Below is an extract from the ReliefWeb coverage:

"TA REACH, 6 September 2011 - Cambodian efforts to contain the spread of malaria have been strengthened by a pilot project using text messaging and web-based technology.

"My work is definitely easier," said Sophana Pich, 41, one of 184 village malaria workers (VMWs) now trained in three provinces (Kampot, Siem Reap and Kampong Cham) since the project launch earlier this year.

She typically diagnoses five to six cases of the often deadly virus each month during the rainy season between May and October.

"Before, it would take a month before this information was reported to the district health level. Now it's instantaneous," the mother-of-three said from her home in Ta Reach, a village of 200 households in Kampot Province, about 150km southwest of Phnom Penh.

There are close to 3,000 VMSs in 1,500 villages across Cambodia, described by many as the "foot soldiers" in the country's fight against malaria.

As part of a larger US$22.5 million malaria containment effort launched by the government in 2009 and funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the volunteers receive three days of training in the early diagnosis of malaria and treatment.

In addition, they are given a bicycle, a pair of boots, a bag, a flashlight and a cooler box for medicines, as well as a small travel allowance.

Under the pilot scheme now under way, they are also given mobile phones.

Using FrontlineSMS - an open-source software enabling users to send and receive text messages with groups of people - VMSs can now report in real time all malaria cases in their villages to the Malaria Information and Alert System in Phnom Penh with a simple text message, including the patient's name, age, location and type of virus."

To read the full article visit ReliefWeb.