The African Great Lakes Initiative (AGLI) strengthens, supports, and promotes peace activities at the grassroots level in the Great Lakes region of Africa (Burundi, Congo, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda). Here, in our twenty-ninth guest blog post, AGLI Coordinator, David Zarembka, discusses how FrontlineSMS proved a valuable tool for supporting and coordinating peace building efforts during recent election violence prevention in program in Burundi.

AGLI long ago learned that elections, rather than being a time of assessment, change and optimism, can, in the Great Lakes Region of Africa, often be a time of fear, unrest, and violence. Burundi is no exception. A traumatic civil war (1993-2006), instigated in part by the assassination of then president Melchoir Ndadaye, tore Burundian communities apart along “ethnic” lines and traumatized citizens on all sides. Tensions remain high, especially during election times. With this in mind as the 2010 Burundi elections approached, AGLI worked with the Healing and Rebuilding Our Communities (HROC) program in Burundi to develop the Burundi Election Violence Prevention Program.

during recent election violence prevention in program in Burundi.

AGLI long ago learned that elections, rather than being a time of assessment, change and optimism, can, in the Great Lakes Region of Africa, often be a time of fear, unrest, and violence. Burundi is no exception. A traumatic civil war (1993-2006), instigated in part by the assassination of then president Melchoir Ndadaye, tore Burundian communities apart along “ethnic” lines and traumatized citizens on all sides. Tensions remain high, especially during election times. With this in mind as the 2010 Burundi elections approached, AGLI worked with the Healing and Rebuilding Our Communities (HROC) program in Burundi to develop the Burundi Election Violence Prevention Program.

With a grant from the United States Institute of Peace, the project ran from May 2009 until October 2010 in nine communities across Burundi. The Program involved participatory community workshops to help heal trauma and encourage reconciliation. The 720 workshop participants were then organized into eighteen Democracy and Peace groups, two in each community to serve as the basis for observing the elections and preventing election violence in their local community.

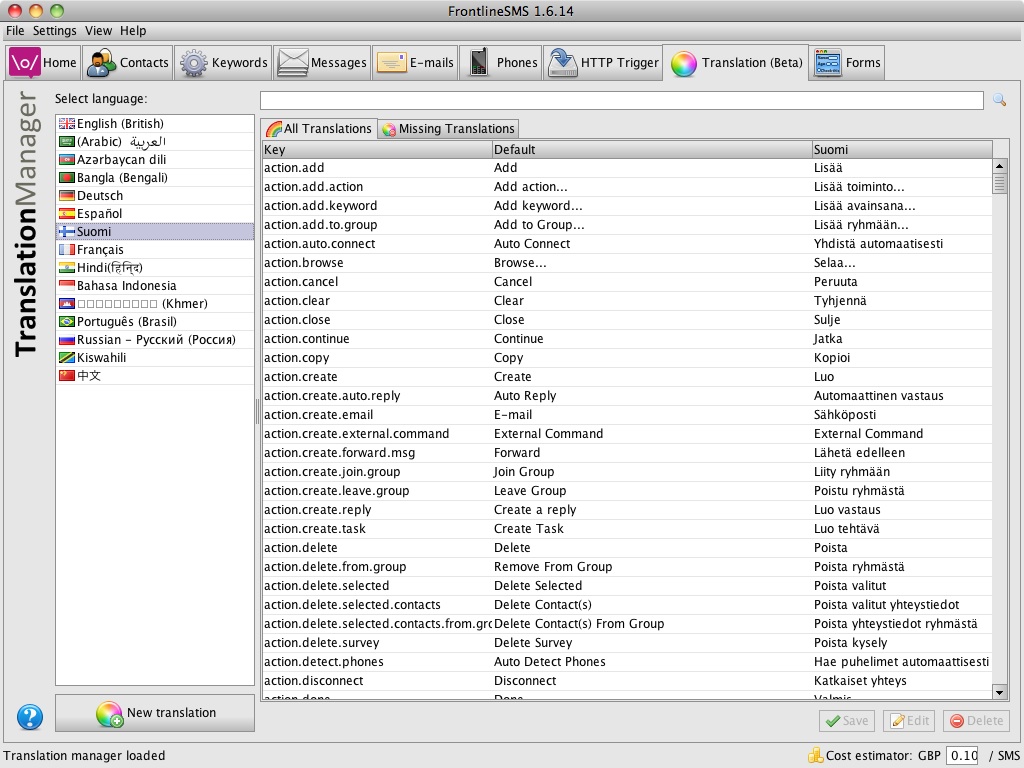

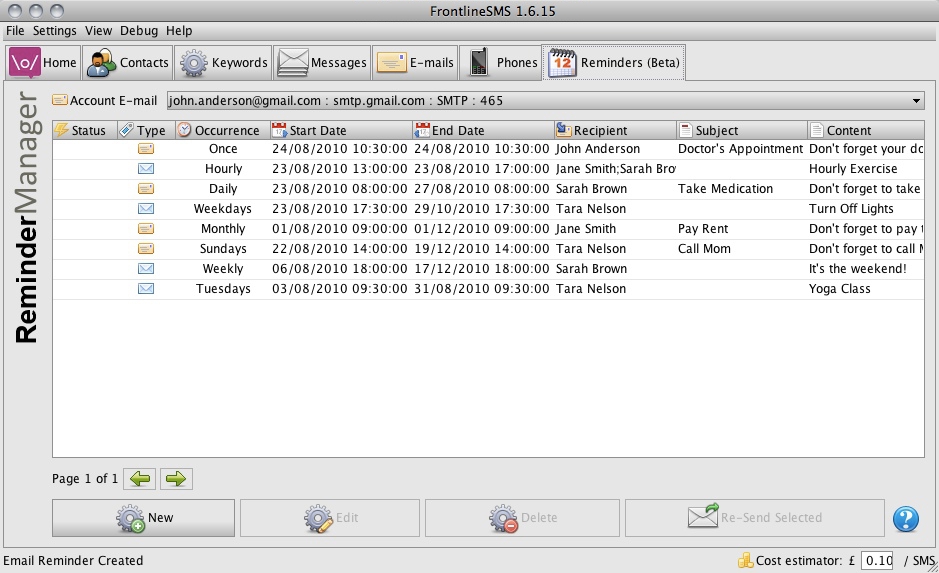

While not part of the original proposal and based in part on the example set by the use of cell phones in Kenya in response to the 2008 post-election violence, staff decided that the program would benefit from taking advantage of recently developed technologies for networking via cell phones. The program staff decided to make use of FrontlineSMS, because it is an open source software program that allows people to send a single text message that is then rebroadcast to other members of a pre-defined set of users. In this case those users were citizen reporters who were part of the Democracy and Peace Groups as well as HROC staff.

Various technical delays and the lack of timely funding meant that the program did not get completely up and running as quickly as we would have liked. One of the challenges was that funding was not available to purchase the phones, and collecting 42 used phones which were donated from the UK and the US was time consuming. In early June 2010 additional funding was secured from Change Agents for Peace, International and used to buy a number of very cheap phones that provided a greater degree of standardization and allowed the inclusion of more participants.

There were 160 citizen reporters who participated in the system. They were organized into nine groups, one for each community, as well as groups for HROC facilitators and staff. Training for the citizen reporters – to explain the basics of how to use the cell phones, how the phones would be used to promote the goals of the project, and how the phones would function with the FrontlineSMS system – were held in each of the nine communities.

There were 160 citizen reporters who participated in the system. They were organized into nine groups, one for each community, as well as groups for HROC facilitators and staff. Training for the citizen reporters – to explain the basics of how to use the cell phones, how the phones would be used to promote the goals of the project, and how the phones would function with the FrontlineSMS system – were held in each of the nine communities.

The skill level of the participants varied, ranging from people who were already familiar with using phones and sending text messages to people who had never used a phone, were barely literate, and had difficulty seeing the letters on the buttons and pressing the small buttons. Another minor challenge was that the FrontlineSMS system was occasionally overwhelmed with text messages, particularly on Election Day, which occasionally created delays.

Based on the record of the texts that were sent between June 25, 2010 and July 24, 2010, there were 735 text messages received from participants; about 12 messages per day. These were then re-distributed, and the system sent out 7,449 messages; about 124 per day.

The most frequent messages were those reassuring people that things were calm, followed by messages reporting incidents such as grenade attacks on polling stations, arrests, or other concerns. They were also used to share ideas with observers about possible irregularities for which they should be alert.

One particularly interesting series of text messages were explained by a participant during the evaluation interviews:

“On the eve of the presidential elections, everything was very tense, the bars were all closed, and the police were on high alert. Then I heard that three people were arrested that evening who we knew were not actually engaged in illegal activities. I texted [another member of the Democracy and Peace Group,], who agreed to follow up on the case with the police. From there, the two of us communicated by cell phones to coordinate our efforts to speak with various local officials and administrators. Eventually we heard from the Commune administrator that if one of us came the next morning we would see that they will be released. Later we heard from one of those arrested that one of the police officers was asking him, “Who are you that you have these administrators suddenly concerned about your status?” So it was really our coordination through the SMS network that helped these innocent people be released without harm.”

This indicates the type of coordination that was achieved through the FrontlineSMS network.

Participants suggested that there were in fact good reasons for having the option of text messaging. One advantage they mentioned was the possibility of privacy. For example, if one is witnessing an event first-hand it may not be possible to inform others by a traditional cell-phone call since people in the vicinity might overhear and might misunderstand the reasons why other people are being alerted, putting the observer at risk.

As with other communication tools, while the FrontlineSMS network enhanced the ways people were able to work together, ultimately the effectiveness of the network was a product of more traditional skills and relationships. The ease of communicating, and the ability to do so in a discrete way may have engaged citizens who would not otherwise have played an active role.

The group networks formed were functional and added to the overall program. Participants found the network useful for sharing information and keeping each other up-to-date. In this way the project set an important precedent for how similar networks might be used in the future.

For further information on how the Burundi Election Violence Prevention Program was organised, using FrontlineSMS as a tool, please see the AGLI Manual for Creating Democracy and Peace Groups to Prevent Election Violence.

We've designed the first ever FrontlineSMS user survey to help us understand what happens after the software is downloaded from our website. Your responses will help us improve the software and make it easier to use, and will let us know how we can better help you incorporate SMS in your work.

We've designed the first ever FrontlineSMS user survey to help us understand what happens after the software is downloaded from our website. Your responses will help us improve the software and make it easier to use, and will let us know how we can better help you incorporate SMS in your work.

A group of companies, including Ushahidi, FrontlineSMS, CrowdFlower and Samasource, collaborated to set up a text message hotline – “Mission 4636” – supported by the U.S. Department of State. The Haitian government collaborated with radio stations to advertise the hotline, and a few days after the disaster, anyone in Port-au-Prince could send an SMS to a toll-free number, 4636, to request help. The messages were routed to relief crews at the U.S. Coast Guard and the International Red Cross on the ground.

A group of companies, including Ushahidi, FrontlineSMS, CrowdFlower and Samasource, collaborated to set up a text message hotline – “Mission 4636” – supported by the U.S. Department of State. The Haitian government collaborated with radio stations to advertise the hotline, and a few days after the disaster, anyone in Port-au-Prince could send an SMS to a toll-free number, 4636, to request help. The messages were routed to relief crews at the U.S. Coast Guard and the International Red Cross on the ground.